Lily Alfred

"I've always been the low man on the totem pole."

In the words of Lily Alfred: "All I knew when I went in to Residential School was Yes, No and Thank you. I didn’t know how to speak English because I lived in Fort Rupert. The only white people there were the ones that owned the store where the Hudson’s Bay used to be. My grandfather Jonathan Hunt used to tell me that he lived in the fort until he was eleven. His dad was George Hunt. My grandfather’s grandfather was Robert Hunt. He married a woman from Alaska. They canoed all the way from Alaska to Fort Rupert. He was the big man at the Hudson Bay Company.

I didn’t know potlatches were outlawed. I remember the first time that I Indian danced. I was 6-years old. There were a lot of potlaches but not very many people like there is today. It was really good. Everything was nice and quiet, like you were in church. Nobody walked around. Nobody went out to buy snacks like they do nowadays. I remember as a little girl, I was at a potlatch. I wondered why my granny was standing there with a little stick in her mouth beside the fire, hands behind her back. She stayed there for quite a while. I asked my mum what she was doing there and my mum said she got caught eating. My grandmother was a big woman. She was a chief. She being punished because she got caught eating. When it was time to eat at the potlatch, those ladies got those big pots and put them beside the fire and cooked the food there, like dried fish and potatoes. And grease.

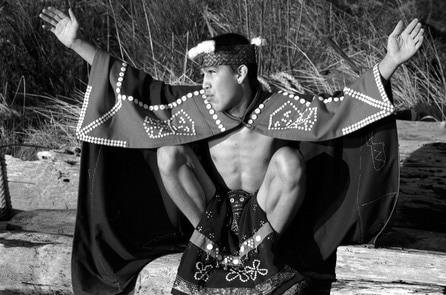

About 4 days before I danced, we were at the Longhouse. All of a sudden they were all banging and singing. This old man was running around looking for somebody. Then he came and got me and took me around the fire 4 times and took me out to a house and said “Take your dress off! Take your dress off!” So I took it off. I didn’t know what the heck was going on. My mum told me when he went back to the Longhouse he had my dress and somebody had killed a seal and he rubbed the dress in the blood and he was kai-yai-ing away. I wasn’t allowed to go out or even look out of the window. I disappeared. When it was time to appear, everybody that got taken out finally showed up and went through the forest. My dad came with me and started putting branches on me, a skirt, a top, a headband and anklets. He said “You know, when your grandmother did this dance, they cut all her hair off. I think I should cut your hair off.” I started crying and I said No, no. Then we all walked toward the Longhouse. One by one we went in and did our dance I had practiced. And that was it. In the evening, we came out again in our regalia. They had put money all over the blanket I had worn. I didn’t know it was money then. I had that dance for a long time. It came from my dad’s mum. I danced quite a bit before I went to St. Mike’s.

My granny was classified as a big chief. She had 3 or 4 uncles that were big chiefs and they had no children to pass it on to so they passed it on to my mum. She passed it on to me. I’ve always been the low man on the totem pole. *laughter*

We took the ferry to Ketchikan to meet our family. When the ferry landed I see all these people coming down the wharf with their regalia on and their drums. I felt like crying. They were our relatives. I didn’t know anything about them.

Now I’m the oldest one on the reserve. I’m old, old, old. *laughter* Life’s too short. Mine, anyhow. I just tell myself, Lily, your days are numbered. Don’t let it bother you. *laughter* "

I didn’t know potlatches were outlawed. I remember the first time that I Indian danced. I was 6-years old. There were a lot of potlaches but not very many people like there is today. It was really good. Everything was nice and quiet, like you were in church. Nobody walked around. Nobody went out to buy snacks like they do nowadays. I remember as a little girl, I was at a potlatch. I wondered why my granny was standing there with a little stick in her mouth beside the fire, hands behind her back. She stayed there for quite a while. I asked my mum what she was doing there and my mum said she got caught eating. My grandmother was a big woman. She was a chief. She being punished because she got caught eating. When it was time to eat at the potlatch, those ladies got those big pots and put them beside the fire and cooked the food there, like dried fish and potatoes. And grease.

About 4 days before I danced, we were at the Longhouse. All of a sudden they were all banging and singing. This old man was running around looking for somebody. Then he came and got me and took me around the fire 4 times and took me out to a house and said “Take your dress off! Take your dress off!” So I took it off. I didn’t know what the heck was going on. My mum told me when he went back to the Longhouse he had my dress and somebody had killed a seal and he rubbed the dress in the blood and he was kai-yai-ing away. I wasn’t allowed to go out or even look out of the window. I disappeared. When it was time to appear, everybody that got taken out finally showed up and went through the forest. My dad came with me and started putting branches on me, a skirt, a top, a headband and anklets. He said “You know, when your grandmother did this dance, they cut all her hair off. I think I should cut your hair off.” I started crying and I said No, no. Then we all walked toward the Longhouse. One by one we went in and did our dance I had practiced. And that was it. In the evening, we came out again in our regalia. They had put money all over the blanket I had worn. I didn’t know it was money then. I had that dance for a long time. It came from my dad’s mum. I danced quite a bit before I went to St. Mike’s.

My granny was classified as a big chief. She had 3 or 4 uncles that were big chiefs and they had no children to pass it on to so they passed it on to my mum. She passed it on to me. I’ve always been the low man on the totem pole. *laughter*

We took the ferry to Ketchikan to meet our family. When the ferry landed I see all these people coming down the wharf with their regalia on and their drums. I felt like crying. They were our relatives. I didn’t know anything about them.

Now I’m the oldest one on the reserve. I’m old, old, old. *laughter* Life’s too short. Mine, anyhow. I just tell myself, Lily, your days are numbered. Don’t let it bother you. *laughter* "

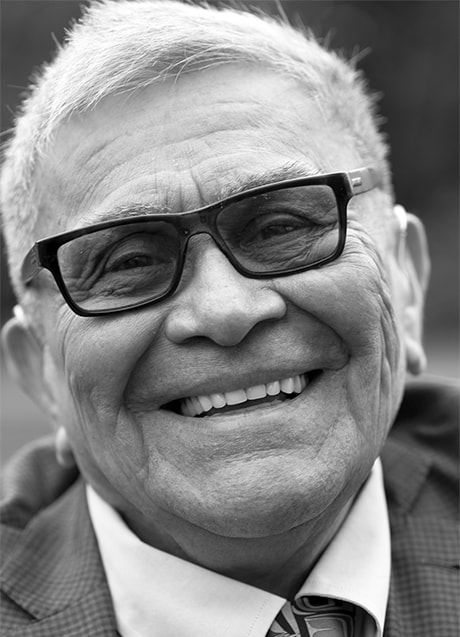

Chief Robert "Bobbie Joe" Joseph

"In spite of what you've done to yourself, I love you."

In the words of Chief Robert "Bobbie Joe" Joseph: "Racism still exists. It’s very subliminal and practiced by many more people than we think. I think it’s something inherent in the human race simply because of our tribes and nations, divided by whatever creates a sort of “ism” toward each other.

Prior to the revelation of the Residential School legacy and its subsequent impacts, I, like all the other former students, simply buried it deep, and didn’t know it resonated in their soul and their spirits. It manifested as dysfunction, anger, despair and hopelessness. When we told these stories, people wanted to find a way forward different from where we had been. I thought “This is really important. This may bring about the change we have desired for all of our lives. It’s the opportunity to work for people trying to find a direction and a new way forward.“ Before that, I had fallen into a life of alcoholism and despair. I lost a wonderful job, a family and children. One day I went home and they were all gone. I didn’t work anymore. BC Hydro cut my power off because I couldn’t pay the bills. I found myself in a dark and deep hole. I ran into a friend of mine. He said “You know, Bobbie Joe, I don’t like what you’re doing to yourself. Come fish with me a day or two. Get out of town.” I knew instantly he had good advice and I said “I’ll go fishing with you.” I found the boat. I don’t remember getting on it or leaving port. Early the next morning I woke up. The crew were still sleeping. I snuck out of the bunk to the very stern of the boat. There was not another human being insight. Just me and the stern of the boat. I fell to my knees and said “God, help me.” It wasn’t a prayer because I was angry at God at that time, right? But as I fell to my knees, the tears just poured out. I couldn’t see through them. As I began to open my eyes as wide as I could, I saw the ocean. I had never seen the ocean like this. Blue, green, coral, energy going through it. I looked over at Vancouver Island on the other shoreline. I saw a forest and it had lightening bolts going through it. I raised my eyes more and I looked toward the heavens and I saw the entire universe and, in the splendor of all I was looking at, I heard this voice say to me “In spite of what you’ve done to yourself, I love you and you are a part of all of this.”

Ever since that time I’ve wanted to be a part of it all. More than that, I want everyone else to be a part of it all. In this work of Reconciliation, we all have to be in it together. We’ve all got to believe in our basic worth and value, to have purpose in our lives. If we stay in our “isms,” far too many of us will be victims of the trauma of marginalization and other things.

Because I was a Residential School student for 11 years, I recognized people wanted to hear from me. I had this experience. I’d been there. I’d experienced all of the pain and suffering. It gave me moral ground to invite people to come in and for us to ask ourselves “Given what we know, the history and the legacy of residential schools, what will we do now?” I worked really hard with a lot of people. I and three other survivors had the honor of sitting with the former Prime Minister for half a day. He wanted to know what we wanted to hear in an apology. I was in the House of Commons when he apologized. It didn’t matter that so many people thought he wasn’t sincere. The point was somebody at the highest level of our government said “You know what? We did this to you and we’re sorry.”

It’s so important to know your place in the cosmos. That’s why I got so badly hurt because I lost that sense of who I was and did I even belong. This culture of ours from the time we’re born and then as we grow up, has stages where we’re affirmed and validated, told how precious we are, that we have value, we have purpose and we belong to this greater thing. I was so privileged to be born early enough to hear speakers when it was still a first language for so many. But I think my generation is probably the last to grow up that way."

Prior to the revelation of the Residential School legacy and its subsequent impacts, I, like all the other former students, simply buried it deep, and didn’t know it resonated in their soul and their spirits. It manifested as dysfunction, anger, despair and hopelessness. When we told these stories, people wanted to find a way forward different from where we had been. I thought “This is really important. This may bring about the change we have desired for all of our lives. It’s the opportunity to work for people trying to find a direction and a new way forward.“ Before that, I had fallen into a life of alcoholism and despair. I lost a wonderful job, a family and children. One day I went home and they were all gone. I didn’t work anymore. BC Hydro cut my power off because I couldn’t pay the bills. I found myself in a dark and deep hole. I ran into a friend of mine. He said “You know, Bobbie Joe, I don’t like what you’re doing to yourself. Come fish with me a day or two. Get out of town.” I knew instantly he had good advice and I said “I’ll go fishing with you.” I found the boat. I don’t remember getting on it or leaving port. Early the next morning I woke up. The crew were still sleeping. I snuck out of the bunk to the very stern of the boat. There was not another human being insight. Just me and the stern of the boat. I fell to my knees and said “God, help me.” It wasn’t a prayer because I was angry at God at that time, right? But as I fell to my knees, the tears just poured out. I couldn’t see through them. As I began to open my eyes as wide as I could, I saw the ocean. I had never seen the ocean like this. Blue, green, coral, energy going through it. I looked over at Vancouver Island on the other shoreline. I saw a forest and it had lightening bolts going through it. I raised my eyes more and I looked toward the heavens and I saw the entire universe and, in the splendor of all I was looking at, I heard this voice say to me “In spite of what you’ve done to yourself, I love you and you are a part of all of this.”

Ever since that time I’ve wanted to be a part of it all. More than that, I want everyone else to be a part of it all. In this work of Reconciliation, we all have to be in it together. We’ve all got to believe in our basic worth and value, to have purpose in our lives. If we stay in our “isms,” far too many of us will be victims of the trauma of marginalization and other things.

Because I was a Residential School student for 11 years, I recognized people wanted to hear from me. I had this experience. I’d been there. I’d experienced all of the pain and suffering. It gave me moral ground to invite people to come in and for us to ask ourselves “Given what we know, the history and the legacy of residential schools, what will we do now?” I worked really hard with a lot of people. I and three other survivors had the honor of sitting with the former Prime Minister for half a day. He wanted to know what we wanted to hear in an apology. I was in the House of Commons when he apologized. It didn’t matter that so many people thought he wasn’t sincere. The point was somebody at the highest level of our government said “You know what? We did this to you and we’re sorry.”

It’s so important to know your place in the cosmos. That’s why I got so badly hurt because I lost that sense of who I was and did I even belong. This culture of ours from the time we’re born and then as we grow up, has stages where we’re affirmed and validated, told how precious we are, that we have value, we have purpose and we belong to this greater thing. I was so privileged to be born early enough to hear speakers when it was still a first language for so many. But I think my generation is probably the last to grow up that way."

Intro to Dos Polacas' Book ProjectOur book project is called In Our Hands: The Keepers of the Box of Treasures.

The funds raised through Kickstarter from our wonderful supporters has gone to producing this book, including any additional equipment or travel.

100% of the net proceeds from book sales will go toward Indigenous language education in the Kwakwaka'wakw community. We will not take any royalties or any of the profits from the sale of the completed books. This project welcomes you to witness the knowledge and experience of the elders of the Kwakwkak’wakw people. You will learn from them about resilience, reconciliation and strength.

We are collaborating in this tremendous book and online project with two women steeped in their culture. Andrea Cranmer is a traditional culture teacher and mentor. Pewi Alfred teaches Kwak'wala at the elementary school in Alert Bay and is a traditional dance instructor. They both grew up in the Kwakwaka’wakw culture in Alert Bay, British Columbia learning about their traditions from their mothers and fathers, grandmothers, other family members and their community. As teachers and mentors they have devoted their lives to their culture, passing it on to the next generation. We are very thankful they are working with us, insuring the voice of the project is that of the First Nations community.

|

This is Mrs. Lily Speck (above), an esteemed elder from Alert Bay who Sharon photographed in 2001.

Mrs. Speck was a real lady, held in very high regard and respected as someone who held and passed on the Kwakwaka'wakw cultural traditions and protocol to her family and the wider community.

We thank her family who has allowed us to use this image on a limited basis.

Her image has been the symbol of "In Their Hands" for many years. And now for our Kickstarter Campaign. Gilaka'sla.

|

In Their Hands started 17 years ago

when Sharon was asked by Andrea Sanborn, the U’Mista Cultural Center’s executive director,

to photograph the older members of the community.

Pamela joined her to interview them while Sharon created their portraits.

The result is a book project of intimate portraits of these elders and in-depth interviews.

Please visit click HERE to read how Sharon sees the art of portraiture.

when Sharon was asked by Andrea Sanborn, the U’Mista Cultural Center’s executive director,

to photograph the older members of the community.

Pamela joined her to interview them while Sharon created their portraits.

The result is a book project of intimate portraits of these elders and in-depth interviews.

Please visit click HERE to read how Sharon sees the art of portraiture.

What will you experience by being part of this project?

|

By celebrating the elders, the youth and the earth, we build a bridge stretching between cultures.

Across this bridge travel traditions, healing, reconciliation, strength, stories, spirit, music and mystery. Looking around us, we see that the kaleidoscope of world cultures has not yet turned monochromatic but the threat is on the horizon for many Indigenous cultures. If First Nations cultures are diminished, we are all impoverished. Look at the faces and hands of these older members of the First Nations community. Listen as Kwakwaka’wakw elders share their life experiences. When we grow and learn together, we strengthen each other and celebrate our similarities as well as our differences. We ask you to join us to Accompany us on this fascinating journey |

What motivates us?

Who has guided us in this direction?

First it was Andrea Sanborn, the executive director of the U'Mista Cultural Center.

Now it is our collaborators, Andrea Cranmer and Pewi Alfred.

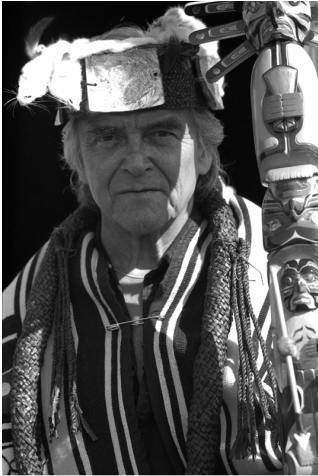

But it has also been the older members of the Kwakwaka'wakw community who have been so generous with their time and encouragement, like Robert “Bobbie Joe” Joseph, Stan Hunt, Maxine Matilpi, Beau Dick, Vera Cranmer, Juanita Johnson and many others.

Now it is our collaborators, Andrea Cranmer and Pewi Alfred.

But it has also been the older members of the Kwakwaka'wakw community who have been so generous with their time and encouragement, like Robert “Bobbie Joe” Joseph, Stan Hunt, Maxine Matilpi, Beau Dick, Vera Cranmer, Juanita Johnson and many others.

What do we expect to accomplish with this project?

In collaboration with First Nations communities, and more specifically the Kwakwaka’wakw community, we are working toward a better future. This project is a model of how non-natives work together with Indigenous peoples to make a healthy planet with courageous youth and honored elders; where reconciliation, collaboration and resilience define our inter-cultural communications.

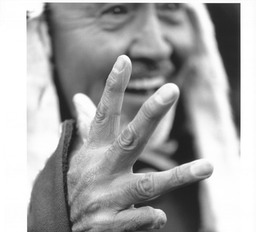

This book project and its accompanying online language resources highlight the resilient spirits of many older First Nations community members. They tell their own stories accompanied in the book by portraits of their faces and hands. In Their Hands provides a platform from which to broadcast the values of these elders’ Box of Treasures.

This book project and its accompanying online language resources highlight the resilient spirits of many older First Nations community members. They tell their own stories accompanied in the book by portraits of their faces and hands. In Their Hands provides a platform from which to broadcast the values of these elders’ Box of Treasures.

With your generous help and support through our Kickstarter, this project will add to work already begun: Indigenous language education, teaching community youth the age-old Kwakwaka’wakw cultural traditions, and involving the community in reconciliation through story-telling and portraits. By engaging non-native people outside of the Kwakwaka’wakw community in these efforts, through the sales of this book, our collaboration will support the continuing growth of this complex, resilient culture.

The Ace Up Our Sleeve

Dos Polacas’ real treasure lies in our unparalleled access to the Indigenous communities of the Pacific Northwest developed over the last twenty-five years. These personal connections allow us to sit at kitchen tables sipping coffee and in carving sheds watching artists at work. Every chance we get, we document the older peoples' humor, stories, knowledge and personalities so they are not lost to the passage of time.

What has been done?

We have suceeded in:

- Making 40 more portraits

- Recording 40 interviews

- Creating more excellent photographs

- And soon we will be publish In Our Hands.

What experience do we have?

Sharon's Background

As a fifth generation artist I am driven by the power of creative images. My camera is not just the tool I use to create photographic portraiture, it also allows me to stand on a bridge, that crosses between different cultures. Through my lens I am fortunate to observe ceremonies, photograph fine art being made, listen while stories and songs are shared and make portraits of those same story tellers and singers. Photography gives voice to my experiences and allows me a personal interpretation of the world.

Spending decades with Native and First Nation peoples of the Inland and Pacific Northwest of the United States and Canada has dramatically affected my attitude towards how and what I see. Through experiencing the diversity of peoples I have learned to recognize the colors, the light and it’s shadow side, of my home, here in the Pacific Northwest, in a very distinct way. Against a backdrop of magnificent natural beauty that is the Northwest Coast these same decades have gifted me with life-long friendships within Native and First Nations communities. Through these dear friends, aunties, and uncles I continue to learn about the richness and drama deeply woven into the daily lives of Indigenous peoples. I am profoundly grateful and honored not only each time I lift a camera and exchange that moment that becomes an image...but also for the joy of presence and connection.

As a fifth generation artist I am driven by the power of creative images. My camera is not just the tool I use to create photographic portraiture, it also allows me to stand on a bridge, that crosses between different cultures. Through my lens I am fortunate to observe ceremonies, photograph fine art being made, listen while stories and songs are shared and make portraits of those same story tellers and singers. Photography gives voice to my experiences and allows me a personal interpretation of the world.

Spending decades with Native and First Nation peoples of the Inland and Pacific Northwest of the United States and Canada has dramatically affected my attitude towards how and what I see. Through experiencing the diversity of peoples I have learned to recognize the colors, the light and it’s shadow side, of my home, here in the Pacific Northwest, in a very distinct way. Against a backdrop of magnificent natural beauty that is the Northwest Coast these same decades have gifted me with life-long friendships within Native and First Nations communities. Through these dear friends, aunties, and uncles I continue to learn about the richness and drama deeply woven into the daily lives of Indigenous peoples. I am profoundly grateful and honored not only each time I lift a camera and exchange that moment that becomes an image...but also for the joy of presence and connection.

Pamela's Background

The job of documenting elders belongs not only to the photographer’s eye but also to the writer’s words. The Kwakwaka’wakw elders talk to me and I listen, recording their voices, using their stories to strengthen vital cross-generational and cross-cultural exchange. Sharon and I have worked together on many smaller projects since 1997, when we produced the publication Opening Hearts about the Raramuri people (Tarahumara) of the Copper Canyon of Mexico.

For Opening Hearts, I wrote the background pieces and sidebars, transcribed interviews, and assembled the pieces for publication. I put the complex culture and history of the Raramuri people into a context that allowed for non-Raramuri to begin to understand this tribe’s self-imposed isolation from the Mexico around them. Since then we have worked on numerous projects large and small. For In Their Hands, my role is to not only capture the elder’s spoken words but create the interview’s context on both an intimate and universal scale in as few words as possible. I bring context and a written beauty to Sharon's photography.

The job of documenting elders belongs not only to the photographer’s eye but also to the writer’s words. The Kwakwaka’wakw elders talk to me and I listen, recording their voices, using their stories to strengthen vital cross-generational and cross-cultural exchange. Sharon and I have worked together on many smaller projects since 1997, when we produced the publication Opening Hearts about the Raramuri people (Tarahumara) of the Copper Canyon of Mexico.

For Opening Hearts, I wrote the background pieces and sidebars, transcribed interviews, and assembled the pieces for publication. I put the complex culture and history of the Raramuri people into a context that allowed for non-Raramuri to begin to understand this tribe’s self-imposed isolation from the Mexico around them. Since then we have worked on numerous projects large and small. For In Their Hands, my role is to not only capture the elder’s spoken words but create the interview’s context on both an intimate and universal scale in as few words as possible. I bring context and a written beauty to Sharon's photography.

We speak about the world in the same way. Sharon uses imagery, Pamela uses words.

Our goal is to have 90% of the words in our book be from interviews. You will read the words of the Kwakwaka’wakw community explaining their culture, not our words.

This online part of the project will supplement Kwak’wala language education. Whenever possible, Pamela records stories in both the speaker’s native language and in English. These recordings will be available through a weblink.

Our goal is to have 90% of the words in our book be from interviews. You will read the words of the Kwakwaka’wakw community explaining their culture, not our words.

This online part of the project will supplement Kwak’wala language education. Whenever possible, Pamela records stories in both the speaker’s native language and in English. These recordings will be available through a weblink.

Book Project Summary

- Approximately 1,000 books will be published

- Each book will contain 150 pages of intimate black and white portrait photography of the Kwakwaka'wakw Elders by Sharon

- Additional stunning photography of the Pacific Northwest coast by Sharon

- Personal, in-depth interviews and stories, recorded by Pamela, transcribed from recordings

- Additional information on the Kwakwaka’wakw culture to be provided by First Nations community members, edited by Pamela and community members

- A dedicated webpage with recorded stories in both English and Kwak’wala will be available for free

Additional Information

The funds raised through Kickstarter will go to producing the book, including any additional equipment or travel. 100% of the net proceeds from book sales will go toward Indigenous language education in the Kwakwaka'wakw community. We will not take any royalties or any of the profits from the sale of the books.

T h i s i s o u r g i f t.

We have been supported in this project by

T h i s i s o u r g i f t.

We have been supported in this project by

- the U'mista Cultural Center and Museum in Alert Bay, British Columbia

- the Burke Museum in Seattle

- the University of British Columbia's Belkin Gallery

- the Bill Reid Gallery in Vancouver BC

- Lindblad Expeditions

Years of creating portraiture and recording interviews with the Kwakwaka'wakw community has gifted us with the portrait photography like you see here below. We are very thankful to all the older community members who have allowed us to photograph them and record their voices.